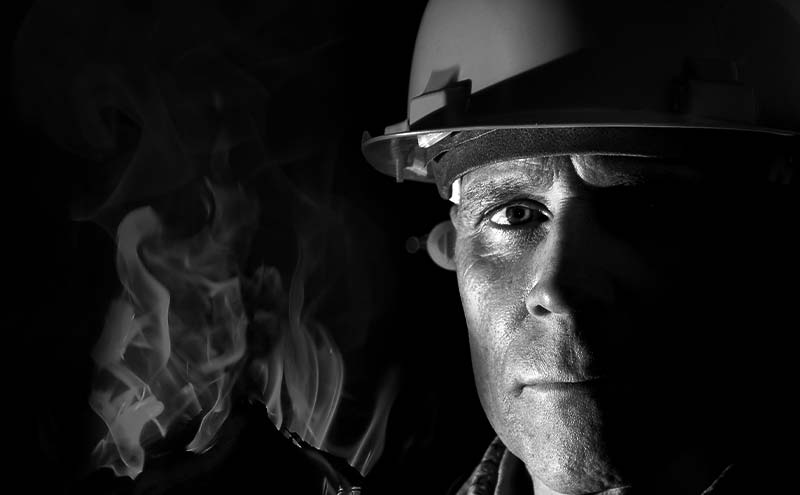

Although it occurred two decades ago, the incident still shakes me today. The smell, the stress, the uncertainty – my body remembers what my mind tries so hard to forget.

Setting the Scene: The Fire

It was 5:00 PM one summer’s day in inland New South Wales, Australia – knock-off time for most people and almost shift change. A Toro 500D Load Haul Dump (LHD) Loader was refuelling, very much routine operations until a small spark and a splash wreaked havoc. The flames quickly grew below the gridding and up into the fuel tank.

The fuelling station was located in a disused access to the 36 Level Stope known as 6 Access. It was a dead-end, unventilated except by diffusion of air from the incline.

It’s unknown whether fuel on the jump start or whether the electrics were kept on was the ignition source, but multiple events collided to create the fire. A broken handle caused fuel to begin overflowing; the onboard fire suppression system failed; one fire extinguisher ran out, and then the second extinguisher failed. Even the closest phone ceased operating.

With each series of unfortunate events, the fire burned stronger. Attempts to extinguish soon became feeble as the flames encased the loader and reduced it to nothing but a charred skeleton.

Heat and smoke blackened the tunnels while emergency protocols were actioned.

A Waiting Game

I was located in the maintenance bay on the 36 level with others; we were trapped underneath it all. With the fire raging so close and smoke in the tunnels, our options for escape were limited; wait in hope or risk the walk – there were no refuge chambers to retreat to.

The smoke was thick, so risking the walk meant you’d need a self-rescuer, which came with its own issues. We all knew they had a history of not working, and if they did work, it was a very uncomfortable experience as the chemicals burned the throat and mouth – no one wanted to have to try to use one. The worst part, we knew there weren’t enough self-rescuers to go around.

We just sat and hoped we would be OK. But, I’ll admit I was bloody scared.

I can’t recall how much time passed, but every minute was agonising. Waiting took its toll, and you could see the anguish and panic in each other’s eyes.

But, we continued to wait, watching for smoke and listening for the all-clear.

The Others

The fire trapped several men; their recount is provided in an incident report and made publically available. Each survived the extenuating circumstances, including the exposure to smoke and high temperatures for over two and a half hours.

To help prevent further events from happening and encourage open communications, we share a collection of four stories: Jack, Alex, Mark and Ben.

After calling in the fire, the load operator and another mine employee, named Jack, were compelled to assist their colleagues they knew were working above the fire. They grabbed six oxygen self-rescuers, commandeered a jeep and attempted to drive past the fire.

It soon became clear the smoke was too thick. Barely seeing over the front of the jeep, the car struck the side of the wall and tipped. Jack fell onto the loader driver momentarily winding him.

Defeated and knowing there was little more he could do, the loader driver returned to the maintenance bay on the 36 level. Jack, on the other hand, donned a self-rescuer and made his way up the incline on foot, firstly running, but soon crawling and clinging to the wall.

By the time Jack made his way to 7 Access the heat and fumes were blinding. His self-rescuer was performing. Yet, he continued on.

Up ahead, Jack could hear cries for help. Jack had stumbled across Alex, who seemed like he had just regained consciousness. He sat with Alex, checked to see if he was ok, though barely stable himself.

The two were resting when Mark came clambering through. Everyone was momentarily relieved. Though Jack tried to explain they needed to go up, Mark continued down. Jack and Alex tried to follow but neither could stand, so they stayed.

Overcome by dizziness, Jack could feel himself succumbing to the inevitable. Memories began to flash before him. He gathered what little he had left and decided to make for the spray drive.

Jack soon became lost. He was realised he was going down instead of up. Disorientated he began scouring the walls for familiar markings. First, he found a sandfill pipe, then a gate end panel with 7A – Jack knew his location and that there was an air hose on the other side of the drive. Relieved he crawled over and cut it open. Fresh air.

It wasn’t long before Jack heard a cry. Alex had moved; he was close. Jack crawled his way towards him and dragged Alex over to another section of the air hose cutting it open.

They thought no one knew they were there.

Jack went for help; Alex stayed.

With a mixture of crawling and walking, Jack made his way up the incline towards the spray drive. His legs began to lose function and a giddy euphoria took over. Only metres away from the spray drive; Jack was dehydrated, deoxygenated he was becoming more out of it.

Ben pulled Jack into the spray drive. Jack collapsed.

Once he got his breath back he cooled himself off under the chilled water sprayers; his body was boiling. Jack and Ben stayed in the spray drive; waiting.

They were later discovered by three persons from the rescue crew, one of which escorted them to 11/12 Access out of the smoke. Jack let the rescue team know where to find Alex. The two others went to search for him.

Mark was loading dirt on Access 9 when the smoke engulfed his Toro500D. Pausing in the cabin, he waited for it to pass. Yet nothing changed. So, Mark put on his cap lamp, and self-rescuer got out of the cabin and decided to get out.

By the time Mark had reached the end of the loader, his eyes were burning; he could not see and could not breathe. Removing the self-rescuer, Mark took his sweat rag, dropped to the floor and began crawling.

Low to the floor, Mark managed to find the air and water hoses; he followed them out of Access 9.

Mark thought no one knew there is a fire.

Thinking the fire originated on Level 32, Mark made his way towards the fresh air bay on Level 36. As he headed down, he felt himself become overwhelmed by the fumes but convinced himself to keep going.

Mark made his way to the spray drive – finally, some fresh air. But, the smoke remained. With no change in the air, Mark again was convinced the fire was above and, with time-critical, he continued down. He scrambled for any sign of an air valve.

Mark heard calls for help – it was Alex and Jack.

By this time, all men were suffering from the heat, intense smoke inhalation and unknown exposure to carbon dioxide. Talking became difficult; it was exhausting, painful and barely comprehensible.

Jack and Alex said to go up; but, since Mark knew what was it was like above them and thinking the two men must be disorientated, he stuck to his guns.

“I’m going down,” Mark said and left.

Staying low and against the wall, Mark made his way down the decline. Up ahead, he could see the headlights of the overturned Jeep. “This must be the fire.”

Determined he will be ok once he passed the wreckage, Mark went on. As he edged past the jeep, the heat almost knocked him down.

Fatigued, parched and scarcely breathing, Mark finally made his way out of the smoke. He fell in a heap of exhaustion between a rock breaker and zinc stub on Level 36.

It was just after 6:20 PM when the Ambulance Room attendant arrived at Level 36 with a compressed air set, rescue trolley and oxy-viva equipment. Mark received treatment.

Ben and Alex worked together at the 7 and 8 Access, unaware of what was going on below them.

Making his way out of the Access, Ben was confronted with a wall of smoke; it took up all of the drive and was rolling towards them.

Ben was quick to flash his lights at Alex and gestured for him to come over. Then he was engulfed in smoke. By the time Ben walked to the back of the loader, he could hardly see more than a metre in front of him.

Believing Alex was in tow, Ben made his way to the wall and used it to guide him up the incline to the spray drive. At first entry, the air was clear and offered some relief. He didn’t stay long. Concerned for Alex, Ben grabbed his damp sweat rag, held it up to his mouth and made his way towards 7 Access. It felt like acid, searing his skin, his eyes, and burning his throat. Ben moves back to the spray for a brief moment before trying to reach Alex again. He could not reach him.

Now back in the spray drive, Ben was at the edge, hoping for another chance to find Alex. The fumes and smoke soon encroached into the spray drive, pushing him further back. Forced to enter the chilled water sprays, Ben now has to cope with extreme cold.

As time passed, the smoke and fumes abated; cautiously, Ben stepped towards the front of the spray drive, hoping to see Alex. While waiting, he saw the light from a miners cap lamp; it was accompanied by disjointed mumbling. Ben could just make out a figure going around in circles. He reached out and pulled him in before the man collapsed – it was Jack.

Ben and Jack waited at the spray drive for help to arrive.

It was approximately 7:20 PM when the rescue team found them both. Neither of them well but able to walk; they were fitted with oxygen self-rescuers and escorted to higher ground. The rest of the team headed towards 7A Access in search of Alex.

Alex worked close to the 7 Access when he was alerted by a flash of lights and Ben waving for him to come over. Unsure of what was happening, he stopped what he was doing and made his way over to Ben and the loader. Quick to move, Alex started to make his way towards the spray drive, but the smoke was too dense; he lost sight of Ben and quickly became disorientated.

Not knowing which way to turn or what was left or right, Alex dropped to the floor. He pulled a rag from his side and used it to cover his mouth – wishing he didn’t leave his self-rescuer in the tool bag at 8 Access.

He yelled out for help; the only response was the hum of a loader. Alex thought the loader might be what was on fire.

Some time had passed as Alex lay in wait, drifting in and out of consciousness before he heard another cry for help. Jack came crawling up the incline before running into Alex.

Alex and Jack lay in the drive. Down the incline came Mark. The three tried to converse, but exhaustion and confusion took over. As Mark took off, Alex and Jack tried to follow, but both became dizzy.

After a while, neither felt like anyone was coming, so Jack went to find help. Alex could not go any further; he could not inhale any more smoke and began shaking and vomiting.

The heat forced Alex to shed his hard hat and boots as they became too hot to touch. Rocks began falling, and the sound of explosions could be heard in the distance. Unsure of the noise, Alex became hopeful that it was water from someone putting out the fire, so he began to crawl back to the loader near 7 Access.

Weak from hours in smoke, Alex would often need to rest to regain the strength to drag his forward. The rocks tore everything up.

Alex called for help.

Again, Jack was close; sliding over, he dragged Alex to the air hose close to him. He cut it open, and both Alex and Jack inhaled from the air hose. Neither with enough energy to move more than what was needed.

Knowing they could not stay like this, Jack went for help; Alex stayed.

Finally, two of the rescue crew appeared, and Alex was found, just hanging on.

Back to the Surface

Once back on the surface, we were all relieved but concerned about the rest of the boys; no one really knew anything. I can only describe the situation as intense. We all suspected that there would have been fatalities.

Being so close to the incident, I consider myself and the people I was with fortunate. If the smoke fell and the ventilation didn’t move the air the way it did. What if?

The day’s outcomes had the potential to be very different, especially for those affected by the smoke and heat.

Safety in Mining

After what happened, I am more vigilant of refuge chambers, their location, the process to get there, and how they operate. I believe that in this incident, knowing they had a place to go where they were safe and had the resources needed to wait it out would have made all the difference. As it was, no one knew where to go and what to do.

Over the years, the focus on improving emergency response through ERTs and training has been one of the biggest changes.

Safety is above all else. I have held senior positions in many mining houses and have always tried to walk the talk on safety and lead from the front at all times.

There is a side effect to ‘over-proceduralisation’ and not giving enough emphasis on providing the tools to the workforce to make the best possible choices in the work they do. Just having a procedure or policy on paper in hand does not keep people safe.